Textile Manufacturer Titus Salt Lived at Methley Hall from 1858 until 1867 – the appended notes are paragraph from a biography written by his friend the Rev. R Balgarnie of Scarborough

Among many eligible mansions that came under his notice, Methley Park was the one selected, and it is here that he resided for the next nine years, and where various circumstances occurred in his history to which we shall refer in this chapter.

Methley Park had been the seat of the Earls of Mexborough for many generations. It is situated six miles from Leeds on the road to Wakefield, from which it is distant about five miles.

At the time to which we refer, the mansion of Methley had remained untenanted for several years; the roof had become dilapidated, the corridors were damp, and the various apartments musty and cob-webbed; while outside, the courtyard and terrace gardens were over grown with grass and weeds.

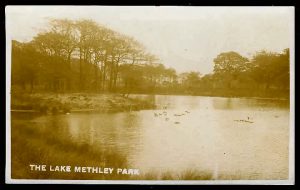

The beautiful park, with its ancient oaks, the herd of deer, the gardens and plantations, had become objects of attraction to excursionists, who roamed whither they listed, sometimes surreptitiously carrying off shrubs and flowers, or leaving names cut on the leaden roof of the mansion, as their only claim to immortality.

It was painfully evident that everything was out of gear on the estate, and that some enterprising tenant was needed, whose capital and energy might restore it to its former condition. Mr. Salt was offered a lease of the place, at an almost nominal rent, which offer, after much deliberation, was accepted, and he at once instructed his architects to make the necessary preparations for his occupancy. This was a herculean task to be accomplished in a limited time, but in the execution of it, no expense was spared to render the lordly mansion worthy of its antecedent history.

As we accompanied Mr. Salt in one of his visits to Methley Park while these preparations were going forward, it is as an eye-witness we refer to them, and to the striking contrast which their completion afterwards afforded.

The mansion was then in the hands of a little army of joiners, bricklayers, painters, gilders, and cleaners, all under the supervision of Mr. Lockwood. The terraces and gardens were in course of transformation from the aspect of a wilderness to that of a paradise.  The park was being thoroughly drained and surrounded by iron fences to keep the deer from straying, while throughout the whole estate there were manifest signs that the reign of desolation was drawing to a close. In a few months all was ready for the migration of the family thither, which event took place about the end of 1856.

The park was being thoroughly drained and surrounded by iron fences to keep the deer from straying, while throughout the whole estate there were manifest signs that the reign of desolation was drawing to a close. In a few months all was ready for the migration of the family thither, which event took place about the end of 1856.

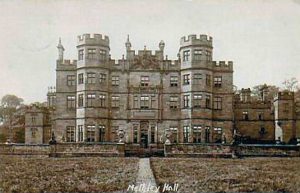

Let us follow Mr. Salt and his family to Methley Park, and enter the house where they have taken up their new abode. The reader who has travelled from Leeds to Normanton by the Midland Railway will have observed the beautiful village of Methley, through which he must pass, with the noble mansion and park situated about a mile to the right. It is built in a castellated style, of light stone, and adorned with towers and battlements.

The entrance-hall is of more ancient date than the other parts of the building, and with its old oak panelling, mullioned windows, stained glass, and organ-loft, gives the impression, at first sight, of an ecclesiastical edifice; but a glance at the walls dispels that impression, for they are hung with old armour and trophies of the chase.

It is needless to say that the new abode was furnished with all the elegance and luxurious taste that wealth could command. One circumstance may here be mentioned as illustrative of Mr. Salt’s personal character; he said “I want my house made as attractive to my sons as possible, that they may not have to seek amusement from home.” Hence, every provision was made for in-door and out-door amusement and recreation,—such as workshop and billiard room; shooting, riding, fishing, &c.

By this change of abode he was now further removed from his “works,” the distance being about twenty miles. Still, when business required his presence, this was no obstacle, and the time of his appearance there was always known. Those of his sons who resided with him, and were partners in the business, generally preceded their father thither. Thus relieved of many duties, he was enabled to attend more to matters of a public kind, amongst which, those connected with parliamentary life claimed his attention.

During the session of Parliament, his seat in the house was always occupied, and his name found on every division list. But within the walls of St. Stephen’s his voice was never heard, except on some formal occasion, such as the presentation of a petition. To him, it was a scene widely different from that with which he had been long familiar. Speaking had always been his weak point; but here it was the chief business.

Early rising and retiring had been the rule of his life, now the long sittings, the heated atmosphere, irregular hours, both of diet and sleep, the exciting debates and divisions, were enough to exhaust any man’s energies, much more his, so unaccustomed to such an experience. In the House of Commons at that time, several of his personal friends had seats, such as Cobden, Bright, Crossley, and Baines. Palmerston, Russell, Gladstone, and Disraeli, were then conspicuous as statesmen. To be associated with such men was, doubtless, a great honour, but it could not compensate for the broken sleep, the shattered nerves and gouty twinges, from which he so frequently suffered. But how thankful he was, when an opportunity occurred, to escape from the excitement of parliamentary life to Yorkshire! to see how business proceeded at Saltaire, or to rest amid the quiet scenes of Methley!

His second daughter, Fanny, fell into declining health. The first cause of anxiety in reference to her state, occurred at Scarborough, where she was seized with slight hemorrhage from the lungs. From this period it was evident that great care would be needed to prolong her life, and every means that skill and love could devise for that purpose, was brought into requisition. Amongst these was a sojourn at Pau and St. Leonard’s, during two successive winters, with several members of her family. Sometimes the fond hope was cherished that the insidious disease was arrested; at other times, the hectic flush and diminished strength dashed that hope to the ground.

Methley Park was especially attractive to her. Its secluded walks she loved to frequent; but much as she enjoyed the beauty around, it seemed rather to point her thoughts and affections upwards, than bind them to earth. We stood with the father that day at the grave of his daughter, and drove back with him to Methley, when the funeral service was over. On our way, his thoughts seemed to linger by the tomb he had left, for once he said, with much emotion, “ I could have lain down beside her.” In response to the remark that this visit to Saltaire had been a very sad one, “Yes,” he said, “the only sad one there I ever had.”

Sometime after this painful visit, we came back with him to Saltaire; and this was not an occasion of sorrow but of joy. He had long been in the twilight as it were; hesitating and halting between Christ and the world. Blessed trouble, that had brought him to see, that full decision for God is the only way of peace and safety! It was, therefore, as a declaration of his faith in Christ that he went to Saltaire, that, with other communicants, he might partake of the Lord’s Supper for the first time. It was a day never to be forgotten. Early on Sunday morning we set out from Methley in the family omnibus, his wife and daughters being with him. On the way thither, hundreds of tracts were given away or dropped for the villagers to gather.

Shall we not describe another service that took place in the evening, after we returned to Methley? In the entrance-hall of the mansion all the people of the estate, together with those of the household, were gathered. It was an unusual sight, in that ancient hall often familiar with scenes of another kind. There, gardeners, and grooms, gamekeepers, and footmen, gatekeepers, and domestics of various grades, were met to worship God.  Those who could not be accommodated in the centre of the hall occupied the steps of the great staircase; while on the oak dais, where in olden times the lord of the manor had feasted, with his retainers seated below him, sat a Christian family to mingle their voices in thanksgiving with their servants. And when the story of redeeming love was preached, it seemed as if many eyes were eager to gaze upon the Divine Sufferer, and willing hearts ready to crown Him as their King.

Those who could not be accommodated in the centre of the hall occupied the steps of the great staircase; while on the oak dais, where in olden times the lord of the manor had feasted, with his retainers seated below him, sat a Christian family to mingle their voices in thanksgiving with their servants. And when the story of redeeming love was preached, it seemed as if many eyes were eager to gaze upon the Divine Sufferer, and willing hearts ready to crown Him as their King.

The Congregational Church nearest to his residence was at Castleford, a town situated about four miles from Methley, and noted for its glass bottle manufacture. The congregation there consisted chiefly of workpeople, who met for worship in a public hall. Mr. Salt felt it his duty from the first to identify himself with this little Christian community, and to aid them in every possible way. From the time of his coming amongst them their strength increased, their hearts were cheered, so that steps were soon taken to erect in the town a suitable church, towards which he and his family largely contributed.

The foundation stone was laid by Mr. Salt, on which occasion many guests were invited to Methley. We well remember how sensitively he shrunk from the duty imposed upon him at the public ceremony, and the apparent relief he experienced when it was over. The church was opened by the Rev. James Parsons, then of York, whose fame as a preacher stood pre-eminent. Of the congregation at Castleford, the Rev. Henry Simon was the respected pastor until he received a call to a larger sphere of work in London.

Mr. Salt was no sectarian bigot, who could see nothing good outside the pale of his own communion. He was ever ready to encourage other Christian denominations in their “work of faith and labour of love”; and the liberality of his heart was not only manifested in gifts of money, but in other Christian acts, that indicated a spirit of charity towards those who, though differing from him in forms of government, were one in Christ.

As an instance of this spirit, he very regularly on Sunday evenings, attended Methley Parish Church, which was within walking distance of his residence. With the rector, the Hon. and Rev. P. Y. Savile, (son of the late Lord Mexborough,) he was on intimate terms of friendship, and was a liberal contributor to the parochial charities. Perhaps it was from this circumstance, that some persons at the time concluded that Mr. Salt’s principles as a Nonconformist were changed. But it was not so. It was rather that the higher principles of religion were exemplified, especially that of Christian love, without which all mere forms of worship and ecclesiastical polity are vain.

Perhaps it was from this circumstance, that some persons at the time concluded that Mr. Salt’s principles as a Nonconformist were changed. But it was not so. It was rather that the higher principles of religion were exemplified, especially that of Christian love, without which all mere forms of worship and ecclesiastical polity are vain.

That he held his convictions firmly at this time, was strikingly manifested in a letter which he wrote to the bishop of the diocese, who had applied to him for aid in a church-building scheme. Thinking that the bishop might have imagined he had become a member of the Establishment, Mr. Salt courteously replied, “I am a Nonconformist from conviction, and attached to the Congregational body. Nevertheless, I regard it as a duty and a privilege to co-operate with Christians of all evangelical denominations, in furtherance of Christian work.” Would that such a spirit might universally prevail!

Frequently he made a special journey to Scarborough to attend the committee meetings, returning by the last train to Methley, which he could not reach till midnight.

The Congregational churches of Scarborough were not the only recipients of his liberality. The Baptists and Primitive Methodists shared it. To the Royal Sea-Bathing Infirmary, the Dispensary, the Mechanics’ Institute, the Cottage Hospital, he was a generous benefactor.

When disaster befell the sea-faring portion of the community he was prompt to aid them. It was in connection with them that a touching incident once occurred at Methley, of which we were cognizant. The Leeds Mercury of one morning contained an account of the upsetting of a boat on the previous day at Scarborough, when two fishermen were drowned. At family prayer the widows and orphans were specially commended to God. When we rose from our knees he seemed much affected, and, taking a ten-pound note from his pocket-book, he said “Give them that.”

Those who have seen his pocket-book so often brought out, when his bounty was to be dispensed, might almost wish it had a voice, for it would reveal the heart of the owner, by deeds, which in words cannot be expressed. The supply of bank notes which it contained, we sometimes called his “tracts,” and which, in their distribution, carried blessings both to the bodies and souls of men.

But let us glance at his domestic and social life, at Methley. The younger children were then about him, and in their pastimes he found relaxation and delight. When little children were sojourning there, he loved to become young again, and to take part in their childish sports. On one occasion, we remember him heading a juvenile procession in the hall and marching to the unmelodious sound of the fire-irons, he being chief musician and leader. When Christmas came, and both children and grandchildren met under the parental roof, his domestic felicity was complete. And when the yule log blazed and crackled on the capacious hearth, (which seemed to have been originally constructed for the purpose,) and the old baronial hall became familiar, once more, with scenes of festive mirth, the echoes of olden times were revived. Methley, at that time, was seldom without guests, and its hospitalities were dispensed with characteristic generosity.

The late Earl of Mexborough, who then resided on the estate, was occasionally invited to join the social circle, which he enlivened by his personal reminiscences of the home where his own life had been passed. Among the guests there once happened to be a distinguished group, consisting of Owen Jones, Digby Wyatt, and Sir Charles Pasley. In the course of the evening the conversation turned upon art and literature, in which several of the guests took part. The host was a silent, but not uninterested listener. The “flashes” of his silence were sometimes equivalent to an articulate speech in conversation. The last-named gentleman, turning to the host, said “Mr. Salt, what books have you been reading lately?” “Alpaca,” was the quiet reply; then, after a short pause, he added, “If you had four or five thousand people to provide for every day you would not have much time left for reading.”

The late Sir William Fairbairn and other old friends were once invited to dine with him; unfortunately, he was laid up in bed by a severe attack of gout. What was to be done in the circumstances? He would not permit the invitations to be recalled, nor be entirely deprived of the society of his guests; he, therefore, held a levee in his bedroom, and, though suffering considerable pain, his original intentions were carried out as far as practicable.

What were his out-door pursuits at Methley? He was not a great horseman, nor a sportsman; occasionally he would ride out with his children. His chief delight was in the cultivation of fruits and flowers. On his coming to Methley, the vineries and green-houses were rebuilt, and supplied with the most modern means of heating and ventilation. With the botanical names of various plants he had but a slight acquaintance; but their form and colour filled him with exquisite pleasure. The grape and pineapple were his favourite fruits, until after his return to Crow Nest, where the cultivation of the banana, or “bread fruit,” took precedence; yet all these were cultivated not alone, for his personal gratification, but for that of friends —and especially invalids, to whom a basket of beautiful flowers or fruits from Methley was always a welcome boon.

What were his out-door pursuits at Methley? He was not a great horseman, nor a sportsman; occasionally he would ride out with his children. His chief delight was in the cultivation of fruits and flowers. On his coming to Methley, the vineries and green-houses were rebuilt, and supplied with the most modern means of heating and ventilation. With the botanical names of various plants he had but a slight acquaintance; but their form and colour filled him with exquisite pleasure. The grape and pineapple were his favourite fruits, until after his return to Crow Nest, where the cultivation of the banana, or “bread fruit,” took precedence; yet all these were cultivated not alone, for his personal gratification, but for that of friends —and especially invalids, to whom a basket of beautiful flowers or fruits from Methley was always a welcome boon.

The mansion at Methley, notwithstanding its internal beauty and surrounding attractions, had certain drawbacks. It was twenty miles from Saltaire, and therefore inconveniently distant from business. It was isolated from those means of social and intellectual enjoyment to be found in proximity to a large town. Moreover, several members of his family now possessed houses of their own, so that such a large establishment as Methley seemed unnecessary.

When, therefore, it was ascertained that Crow Nest was to be sold, no time was lost in effecting its purchase. Great was the joy of the family, when he returned one day, with the news that Crow Nest was now his own; for around that spot their affections had lingered, and to go back to it, was, to them, like “going home.” Happily, no difficulty was experienced in relinquishing the lease of Methley, inasmuch as the present Lord Mexborough had succeeded his father, and was fortunately in a position to occupy the seat of his ancestors. Such was the mutual desire to meet each other’s wishes, and his lordship’s personal gratitude to Mr. Salt, for the improvements on his estate, that when the valuers appointed had finished their task, both parties were fully satisfied with the result. Farewell, then, to Methley, where so many interesting events had occurred, some of which have been already woven into this memoir. But when the time of departure came, shadows of regret seemed to flit across the mind of the outgoing tenant, and at the last social party within its walls, he remarked to a friend, “What a pity to leave it all!”