INTRODUCTION

This story was given to me by my grandmother about 20 years ago. It was originally in typewritten form but she told me that it had been published in a local newspaper – although, unfortunately I have never seen that version. I do not know if my grandmother wrote the story over a long period of time or whether it was the result of interviews by the newspaper reporter. I suspect the former as I recall her telling me that it had been typed up by a friend.

I think it gives a fascinating insight into the hard times she and her family endured – particularly in their younger years. It seems incredible now that less than 100 years ago men would WALK 100 miles or more to find work!

Avril Wood

December 1996 I have made considerable efforts to locate Avril since, say 2006 in order to approve publication of this essay but to no avail.

Bill Thackray

I am pleased to be able to report that on 2nd January, 2019 Avril Wood contacted me after locating the article on the Methley website. Avril explained why we were unable to contact her was because she had lived in Hampshire and then moved to Worcestershire. Our search which included contact with the Forest of Dean Archive Group and searches through electoral lists throughout counties in the north of the country revealed nothing. Avril was intrigued to learn that one of our enquiries lead to an Avril Wood in the Notts area. That same lady not only enjoyed the story but also enjoyed reading about the lengths we had gone to in order to locate the originator. Avril is now making further enquiries as to where Ruth is laid to rest.

Bill T

THE FOREST OF DEAN,

GLOUCESTERSHIRE.

by

RUTH MIRIAM ELCOAT

Early in the 1900’s a baby girl was born. Her name, suggested by Rowland – her mother’s brother, a Quaker and a local preacher, was Ruth. “That’s a short name” said Dad. Can’t you find a better name?” “Yes”, said Rowland, “call her Ruth Miriam. Ruth gleaned in the fields and my sermon tonight is about Miriam.”

I was born in a tiny woodsman’s cottage, one bedroom, no running water, no lights, only candle-light, no proper toilet, a gypsy assisted at my birth. The gypsies were our very good friends.The water was collected in a water butt for washing and household use. A zinc bath hung on the wall. Water for drinking was from the well and as a special treat water caught in a white enamel bucket for drinking. It took over an hour to catch a bucketful, so the bucket had to be taken to the spring and left. If one of the gypsies came for water and the bucket was full, they would move it and put their bucket in its place. They were always very careful not to knock over the bucket.

The fire for heating water and cooking was by peat and hollywood. There was a great amount of hollywood and peat, which was cut in squares like we cut grass sods and stacked to make walls. There was no coal. The oven was like a coal bunker – it was filled with hollywood and when all the wood had been lit and burned to dust, it was raked out , the oven whitewashed and all was ready for baking. First bread, then pastry and cakes. What a performance, how would women of today cope? They even have a machine to beat an egg!

Our transport into Cinderford or Ruardean for shopping about once a month was by governess carriage with brown leather seats and a step at the back to enter and drawn by ‘Joey’, a cross-bred donkey and mare. He was very willing and a good little worker. ‘Joey’ was a gift from the gypsies, they bred all their own horses and their caravans were things of beauty. They were very hard working people, the women made lace for tablecloths and covers and pillowcases, the men made pegs to sell, picked hops to make beer and sold pots and pans. I often think of a little poem gran learnt me: –

“I wish I lived in a Caravan, with a horse to drive like the peddler man.

Where he comes from nobody knows; or where he goes to, but on he goes.

He has a baby brown and they go riding from town to town.

Pots to sell, pans to mend, as he clashes the basins like two bells.

Tea trays all arranged in order, plates with the alphabet round the border.”

The pans were mended with metal discs of cork centres with a hole in the middle. Dad chopped wood for Beauty who was blind and as Dad complained of his wrists being cold she knitted him a pair of cuffs to keep out the cold. Into the wool she knitted over 2000 beads. I still have the cuffs knitted with rough wool. We had a broody hen. The gypsies heard about it, so they brought Mother a clutch of goose-eggs for the hen to sit on and eventually we had a set of little goslings.

We had loads of fruit, Victoria plums, Perry pears, (they made perry – a kind of champagne) and eating pears. They realised about a penny a pound after the transport to the station was paid for. The rest of the fruit we could not use was put on the compost heap for manure. There was very little work to be had.

The tin mines were closed, and that only left forestry work – the Queen’s oak trees. The trees were mostly oak., they were used for the big Battleships. Dad was getting restless. He came up to Yorkshire for work. He walked the ninety three miles to Normanton to try for work in the coal mines. There was no work to be had at Whitwood, Glasshoughton or Pontefract. So he went to see Aunt Sarah Gibbs at Normanton, bought a bunch of violets and put them on my sisters grave, Lavina Elcoat. Lavina was born 1892 and died 1893. He said goodbye to Aunt Sarah and set off North to seek a job.

He walked to Yarm, Middlesborough, Stockton on to Marske, Skelton. Still no work in the walk-in coal mines in Marske. So on to Lingdale where he was lucky, there was work. A house, painted, freshly papered and the money for the furniture to move by train from the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire. So Mother packed up the furniture and we moved house to Moorcock Row, Lingdale, North Yorkshire. We could see Saltburn and the big ships just sitting up in bed in the front of the house, and at the back of the house we could see the moors purple with heather and golden gorse. Well, that job only lasted just over twelve months and dad was given 30/- to take our furniture to another job from Peas and Partners, Iron Stone Mines,

So on to Lingdale where he was lucky, there was work. A house, painted, freshly papered and the money for the furniture to move by train from the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire. So Mother packed up the furniture and we moved house to Moorcock Row, Lingdale, North Yorkshire. We could see Saltburn and the big ships just sitting up in bed in the front of the house, and at the back of the house we could see the moors purple with heather and golden gorse. Well, that job only lasted just over twelve months and dad was given 30/- to take our furniture to another job from Peas and Partners, Iron Stone Mines, Lingdale. So back to Castleford, but Dad came on the train with us. We lodged with Aunt Kitty Gibbs. Dad soon found another job at a pit near Hunslet but that didn’t last long, there was a strike. We lived in a house near Church Lane off Pepper Road, Hunslet.

Lingdale. So back to Castleford, but Dad came on the train with us. We lodged with Aunt Kitty Gibbs. Dad soon found another job at a pit near Hunslet but that didn’t last long, there was a strike. We lived in a house near Church Lane off Pepper Road, Hunslet.

I went to Hunslet school with the strike being on there was no money, I was allowed to take a pot to school .We had two thick slices of jam and bread and for breakfast cocoa, peas pudding but no meat. The mixture was made with lentils that was for dinner. Then before we came home we had tea, two slices of jam and bread and cocoa. All the kids thought this was fine and treated it like a party.

We had to stay after the strike until we straightened the rent up, then Dad got a job at Methley Junction pit. Houses were easy to get, we had a house at Wood Row, Methley – Westmoreland’s Yard (The yard in question was in fact Hollings’ Yard but I suspect Ruth would have referred to it as the name of the owner of the property). We used to walk to Methley Junction to Mrs Hancocks, a friends house. One night we got home very late. It was dark. Mother was striking matches to light the lamp, when there was a funny noise – a shushing noise. She lit the lamp quickly to see swarms of beetles and cockroaches scurrying away. There was nothing much we could do, only go to bed. We didn’t fancy anything to eat. Next morning mother got out the ammonia, put the bottle full in hot water and went round the bottom of the walls. That brought the beetles out for air. There were hundreds of them lying on their backs with their legs on the top (my informant relates that some of the properties there were infested with blackclocks and in a later instance all the inside flags had to be taken up in order to eradicate them). Not one, hundreds – all married with large families! We didn’t know the hens would eat the beetles that crawled away. The landlord who owned the houses, Mr Westmoreland, had the hens and he killed and they were eaten. He was taken to hospital with a poisoned stomach and we were to blame, but he got better and everything turned out all right after Mother explained about using the ammonia. Of course, we had a good laugh.

(The yard in question was in fact Hollings’ Yard but I suspect Ruth would have referred to it as the name of the owner of the property). We used to walk to Methley Junction to Mrs Hancocks, a friends house. One night we got home very late. It was dark. Mother was striking matches to light the lamp, when there was a funny noise – a shushing noise. She lit the lamp quickly to see swarms of beetles and cockroaches scurrying away. There was nothing much we could do, only go to bed. We didn’t fancy anything to eat. Next morning mother got out the ammonia, put the bottle full in hot water and went round the bottom of the walls. That brought the beetles out for air. There were hundreds of them lying on their backs with their legs on the top (my informant relates that some of the properties there were infested with blackclocks and in a later instance all the inside flags had to be taken up in order to eradicate them). Not one, hundreds – all married with large families! We didn’t know the hens would eat the beetles that crawled away. The landlord who owned the houses, Mr Westmoreland, had the hens and he killed and they were eaten. He was taken to hospital with a poisoned stomach and we were to blame, but he got better and everything turned out all right after Mother explained about using the ammonia. Of course, we had a good laugh.

We didn’t feel like living in that house so we moved to Green Lane, Methley. What lovely times we had there Trips over the river by ferry boat which brought you out near Newton Lane – halfpenny fare for children, one penny for adults. Then the trips to Coney Moor to see the lantern show. Two pence for adults and a penny for children – unless we could sneak in, which we did many times. The parson had been a missionary so the films were about his travels in the Congo, Africa. They were still pictures.

The Methley Church is very lovely and worth a visit. It had a spire which went to a point and very high, but after one very stormy and windy winter it was thought safer to remove the spire and build a flat top before any damage was done.  Next to the Churchyard was the school a stone building where we could buy a bag of pears for a halfpenny. Then next to the school was the vicarage another grey stone building. No other building on that side of the road.

Next to the Churchyard was the school a stone building where we could buy a bag of pears for a halfpenny. Then next to the school was the vicarage another grey stone building. No other building on that side of the road.

Most of the pits were run by what was called “Butty” which meant a Deputy (boss) and he used to pick so many men to work, the ones left just came home. Dad got fed up with that so we came to Castleford and were lucky to get a house under Mrs Shepherd. There was a little building in the yard of nine houses. It was a wash house, but Mr Shepherd wanted three pence a week extra if the tenants used it. Mother thought three pence was too much, so did the other tenants so the Landlord kept the door locked. I never saw it open. The toilets were horrible middins with two small holes either side of a big hole. one day little Winnie Clarkson fell down the big hole. Mother brought out our zinc bath. We put a screen round and Winnie had a bath in the yard. We had lots of laughs. We were more lucky than the other tenants – we had a toilet that flushed, it cost Mother a penny a week more and was like a great big drain pipe over a hole. When Mother washed then emptied the bowl down the sink it filled a tip-up bowl which frightened me to death. When it went down the toilet it made such a funny noise. I don’t think I ever got used to it.

In 1917 there were two potteries working full-time – Clokies and Gills. I got a job at Clokies. I was a clay carrier but not being so old it was very hard work. I worked there for two days only and left to go to Gills. The boss asked me why I had left I told him it was too hard work for me, the clay was so heavy. He said “I have a nice little job for you”. He gave me a file, showed me a heap of pots and told me “sit on that stool and knock off all the little pieces of rough pot from the bottom of the cups, plates and saucers”. He showed me how to stack the pots. Just like building a wall, and when I had done so many that I was surrounded by them, a man came and cleared them all away to be put in a kiln after having been dipped in “biscuit” – a kind of stuff resembling starch which put a glaze on the pots. They were arranged in bowls and cooked again in the kilns. If the pots had flowers on they had paper transfers put on before the glaze and also put on a machine that spun round to make the gold ring round the top of the cups and plates and saucers.

I had a pot made for me with a flower transfer of roses and violets with my name in gold glaze. Also one made for my brother Rowland, but it is so many years ago I am afraid the pots must have been broken. I worked at the potteries for over twelve months from six in the morning until six at night. The wages five shillings a week. Thirty minutes for my dinner which I cooked on the top of an iron stove which had a pipe for the smoke to go out of the roof top. My dinner was always bacon and egg. I cooked them on a strong plate which I always put in the cracked pottery baskets because if it had been known I was cooking on a plate I would have got into serious trouble with the boss. I think Mother gave me bacon and egg dinner because it who the only meal we had whilst at work. Breakfast was porridge at home about 5.15 in the morning and didn’t I enjoy my tea at six o’clock when I got home at night. I was so happy at the potteries to be working and earning all that money. Mother gave me a shilling pocket money so now I could buy Christmas presents and go to the pictures at the “Empress” for two pence. I had seen a pair of ornaments for Mum with swans and a woodland scene on the front. They were two pence a week for twelve weeks, and a clock with the same scene on for six pence a week for twelve weeks. Lots of the shops had clubs which you could pay weekly but the goods then stayed in the shop until the last payment was made before you could own them.

I worked at the potteries for twelve months. My mates dared me to ask for a rise which I did and the boss sald he would give me a shilling – so now I had six shillings a week. I now had a little sister. Her name, Grace Irene. She was a lovely baby, but Mother was very ill so Dad said “why not go to Aunt Polly’s and take me with her for a holiday.” So I left the potteries going to Aunt Polly’s at Marske by the sea. It was a very sad time because Grace was taken very ill on the train and as soon as we arrived she had to be put to bed. She died within three days and was buried in the little cemetery on the hills with the noise of the sea and the waves dashing up the side of the cliffs. The village children carried her coffin and made lots of wreaths of dock daisies to be put on the grave. I always wanted a sister but it was not to be.

I went back to the potteries to work and as I had Sundays off work I used to spend the afternoon walking to Kippax Hall. Mr Elland was the lord.

Cousin Rose Gibbs was dairy maid. I had tea with the servants and after tea would all go for a walk in the woods. Rose told me the story about the hill and woods.  Mary Pannal was a witch and the people said she had willed the death of the lord of the Kippax Hall in 1593. So she was tried in York Grand Court and sentenced to be burned at the stake on the hill and near the side of the woods that now bear her name – “Mary Pannal Hill” and “Mary Pannal Wood”. When it was time to go home there was always a half pound of very pale cream butter. The lord would not allow caffeine to be used to make the yellow colour most butters are.

Mary Pannal was a witch and the people said she had willed the death of the lord of the Kippax Hall in 1593. So she was tried in York Grand Court and sentenced to be burned at the stake on the hill and near the side of the woods that now bear her name – “Mary Pannal Hill” and “Mary Pannal Wood”. When it was time to go home there was always a half pound of very pale cream butter. The lord would not allow caffeine to be used to make the yellow colour most butters are.

The Hall was lit entirely by candle light. The drawing room had a candelabra in the middle of the room with one hundred candles on. The candles were renewed each day, and the old ones were used in the passages to light the way to the dairy and kitchens. All the floors were stone, also the steps. The curtains were from floor to ceiling red velvet and the carpet very thick red wool carpet. The fire – logs. I thought it was wonderful, when I come to think of it, for the servants.

Across the road from the Hall is Ledston Hall the home of the Wheelers. Most of the owners of the Hall for generations are buried in the most beautiful Ledsham Church. It is well worth a visit. Peacocks parade round the top of the walls and look very majestic when they spread out their wings, or should I say tails. I have wonderful memories of walks round the Hall with Dad. He knew where to find the first violet, the first primrose and pink and white anemones. The first strawberries from which Mother made lovely scented tasted Jam. Then later the raspberries from the woods, and in the autumn the blackberries and Rhodedendrons which looked beautiful. We would collect herbs for Dad’s herb tea; sentry a little pink flower, marsh mallow a lovely pink and red stained colour, woodbitney a yellow flower.

I have wonderful memories of walks round the Hall with Dad. He knew where to find the first violet, the first primrose and pink and white anemones. The first strawberries from which Mother made lovely scented tasted Jam. Then later the raspberries from the woods, and in the autumn the blackberries and Rhodedendrons which looked beautiful. We would collect herbs for Dad’s herb tea; sentry a little pink flower, marsh mallow a lovely pink and red stained colour, woodbitney a yellow flower. Then, on coming, home Dad would say I musn’t forget to show you where the kingcups grow. They were a very large buttercup flower in orange colour. What a wonderful time I had ,very little money, but what a lot of happiness.

Then, on coming, home Dad would say I musn’t forget to show you where the kingcups grow. They were a very large buttercup flower in orange colour. What a wonderful time I had ,very little money, but what a lot of happiness.

I heard they wanted helpers at Ackton Fever Hospital so I went to see Matron, Miss Musson. She was a wonderful person, just like a second mother. We were very young and she treated us all like her own children. If we were not well it was “come to the dispensary” and she would dose us with medicine!

The first world war was on whilst I was at Ackton hospital. A zeppelin glided over the hospital and dropped all his bombs in a field near Sharlston colliery. They were really meant to be dropped on the coke ovens, but someone had an idea to make a bonf ire in the fields to lure any zepps away. Matron gave us an hour off duty to go over the fields to see the hole made by the bombs. It was massive – a double decker bus could have been buried in it.

We had a terrible flu which affected all at the hospital. Matron made me stay off duty for nearly a month and in that time I had light duties. Matron made one ton of jam, I prepared and gathered the fruit, vegetable marrow jam and strawberry, apricot, raspberry, green tomato. I liked the marrow jam best. The marrow had the pips scooped out, peeled and cut in cubes, like oxos then put to cook with one pound of sugar to each pound of fruit, juice of a lemon and root ginger – a small portion of ginger. I liked the marrow jam flan with lots of cream on the top. We had our own gardener, Mr Lewington .Matron liked to garden , but only the flowerbeds. I used to help her but I hated it. She said “don’t worry my girl, I’ll teach you to like gardening” and she did. She liked to grow violas in different colours – mauve for pink roses, yellow for red roses and maroon for white roses.

Two people died during the Flu epidemic – my pal Annie, and Nurse McGeoff.

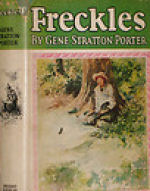

Dr Dixon Harley was the doctor for the hospital. It was always twelve o’clock at night when he visited the patients. I looked after him, ran the water for his bath after he had visited the wards, put him ready a glass of milk, biscuits; and water on saucers for the two dogs. Buller was one and sometimes I went to let him out of the gate and lock it because Mr Lewington was off duty. It made a very long day for me, because I was called up by night nurse at five fifteen, open my window, down for breakfast at five thirty five and on duty at six o’clock after making my bed. But at Christmas what a lovely time. A goose for dinner with all the trimmings, and at the side of my plate a present from Matron – perhaps a pin cushion for my dressing table. A present from Sister Hutchinson,and a present from Dr Hartley. I remember it was a book called “Freckles” by the author Gene Stratton Porter. Dr Hartley had remembered my freckles. I always had a lot on my nose and how I hated them, but could not get rid of them. My wages at the hospital were twelve pounds a year paid once a month, a gold sovereign, uniform, laundry and a fortnights paid holiday.

I remember it was a book called “Freckles” by the author Gene Stratton Porter. Dr Hartley had remembered my freckles. I always had a lot on my nose and how I hated them, but could not get rid of them. My wages at the hospital were twelve pounds a year paid once a month, a gold sovereign, uniform, laundry and a fortnights paid holiday.

Buller died whilst I was at the hospital, he was buried under the wall in the middle of the garden facing the centre of the bedrooms. I stood at my bedroom window and watched him being buried. Dr Hartley loved his dogs. He only had them and he said his family was at the hospital. He brought loads of medical books to the hospital. He said “read these, I’ll make a little nurse of you Ruth” and I think he did. I had very little schooling. I left when I was eleven years of age owing to illness. I had a talk to Matron and told her as my wages were so small I would have to leave.

I got a job at Bradford City fever hospital . I was never so happy there. The wages were thirty-six pounds a year with uniform, laundry and a fortnights paid holiday. I left Bradford City, but the last few months I was there I courted Jim, my future husband. The 1921 strike was on whilst I worked there and Jim and my Dad walked to see me. They were so tired when they arrived, Matron said “see they have something to eat before they go back and you can take time off to see them to the station”. I gave them the money. They got on the train at Bradford and they had to change stations at Ardsley but they must have fallen asleep, so the train took them to Wakefield. That meant a long walk home to Castleford. There were no buses only trams.

I worked at Stanley Royd Hospital after I left Bradford. I loved the work it was mostly on the male side so I was able to have a game of billiards and snooker with the patients. I worked three shifts; afternoons two to ten, nights ten to six, days six to two. Wages £2.5.8d a week for six days on, two days off.

I loved the work it was mostly on the male side so I was able to have a game of billiards and snooker with the patients. I worked three shifts; afternoons two to ten, nights ten to six, days six to two. Wages £2.5.8d a week for six days on, two days off.

I tipped up my wages to Mother. She gave me three shillings pocket money. That went on to 1922 when I left the hospital on Saturday and was married to James Arstall on Sunday at Hightown Church at 8 a.m. on Sunday ist October, 1922. We were very happy but as we had very little money and no furniture, I went out to work selling Tickets and Girdle cakes for which I received five shillings for selling a pounds worth. Sometimes I would earn l0/- (ten shillings) but only odd times.

I went out to work selling Tickets and Girdle cakes for which I received five shillings for selling a pounds worth. Sometimes I would earn l0/- (ten shillings) but only odd times.

Well, with a lot of hard work we got together a nice little home of furniture, also a council house at Airedale in 1924. Miles Grove, No. 24. In that year Kenneth was born – 27 June 1924. He was a lovely baby, and when he was nine months old we got a motor bike and a sidecar so we were able to get about. We changed houses again and lived near the allotments at No. 55 Kershaw Avenue, Airedale. George was born just at the end of a strike in 1926. He was a lovely curly haired baby. I think with the worry of the strike and it lasting so long, I ended up with rheumatic fever. George my youngest baby was taken to hospital. I was in bed two years then in a chair six months, but after that bad luck we were back together again. Jim got to work and he raised the money for a car – a Rover 10. We had a lot of fun, also with the motorbike and sidecar. We would go fishing, swimming, camping and always for a month in the school holidays. George started school when he was 2 years and eleven months. He wouldn’t be away from Kenneth. George was always good at writing and won a first prize for handwriting about ‘kindness to animals’ essay. He was a lovely writer, so neat. I always wished I could write like him, but no luck.

We had a friend, Tucker Field who went with us on lots of motor bike trips. I remember once we watched a ring of rabbits. There was a. rabbit in the middle of the ring and we always said the rabbits were at school! My brother Rowland who had been in the Navy came home on leave. He married Evelyn Dunwell in 1929, July. He went back off leave and Eve stayed with us. Eve loved parties we had some happy times together She loved dressing up Christmas Trees. She made 100 roses to cover up the bulbs , we fixed up the tree, the tree was all ready. “Switch on” we shouted, bang went the bulbs – so off Eve ran all the way to Castleford Woolworths for another 100 bulbs.Second time we were lucky but we didn’t put on the roses we had made with paper.

We moved to another house in Airedale – No. 26, Fryston Road but we didn’t live there long because Kenneth won a scholarship for the Technical College at Whitwood as an Electrical Engineer. Well, we had to exchange houses and moved to No. 50, Rhodes Street, Hightown, Castleford. I didn’t like living there at all.

We had the second world war, the two boys had bunks in the cellar when the air raids were on.

In the war we got another council house –  No. 2, College Grove, Four Lane Ends, Whitwood, Castleford. Kenneth enlisted in the R.E.M.E. He moved not much farther than France and Belgium. George joined the Navy on H.M.S. Nelson. He travelled all over the world. I had a letter every day.

No. 2, College Grove, Four Lane Ends, Whitwood, Castleford. Kenneth enlisted in the R.E.M.E. He moved not much farther than France and Belgium. George joined the Navy on H.M.S. Nelson. He travelled all over the world. I had a letter every day.

He was in hospital with injuries to his ears. I wrote to the War Office to say I had had no letters from him. They replied – “Madam, no news is always good news”; nothing else. Then not long after, the postman knocked on the door. “Come here, a sackful of mail just for you”. There was 36 letters. It was nice to know he was all right. They were both away nearly six years in the war. During that time I lost my two cousins – Aunt Polly’s boys. They were killed in the war.

Mother received an anniversary card for her golden wedding from Rowland, just on time. Alice Mary Gibbs married at Featherstone, James Elcoat 1892, December 25; but Rowland must have been dead at that date because we had a Telegram with the dreaded words “The Admiralty Regrets; Rowland was buried at sea”, which we received just after Christmas. I had no idea where George and Kenneth were. George must have been somewhere near America. He wrote afterwards and told me he had made friends with some American people. They had adopted him after his shin had been hit by shells. He had a choice of going into the Army. He sent me lots of cards from Ireland, the Giants Causeway. Also, very interesting photos of America and a parcel from Ireland – some butter wrapped in a cabbage leaf. The butter was lovely and hard ;as good as being in a fridge. We were only allowed a very little butter and fats on our ration cards.

We were very lucky in war-time. There was only a little damage done to Castleford. A couple of houses had the front part sliced off. You could see the people in bed and they dare not move until the fire wardens came to help them. It was really laughable, but not so funny for the people themselves. Dr Sloane had about 25 fire bombs all in a ring round his house but they were lucky. The only damage was broken windows. An old man running in the house for his cigarettes had his head blown off by the blast from the bombs. The trees growing round the.garden were all lifted up in the air and planted on the rooftops. It was really weird.

Jim was working at the Piston Rings, Hunslet making the rings for the planes. He had left the pit owing to ill-health. He was taken very ill and brought home. Then after being driven home ill a second time he was given his cards. We had very little money so I wanted to go back to the only work I knew – the hospital. Jim didn’t like the idea of me working and said so, and that he married me to look after me. But I wrote to Matron to ask about a part-time nurses job. I got set on and worked seventeen years as part-time nurse. My kind of job – I loved it.

In 1946, I was very ill and Dr Parr advised me to stay off work and go into hospital. I had a major operation and was off work four and a half months. He sent me my wages by cheque and promised me a good job at the hospital when I was able to go back. I made myself go back and was given lovely work such as dental clinic, eye clinic and VD clinic and I just had to order transport to take me from and to the clinics.

When I left the hospital, I was given a nickel silver teapot, sugar basin, cream jug and tray – Swan Brand. I have given them to my grand-daughter Avril on her wedding day.

I now have four grandchildren and one great grandchild. How the years fly past. Grandchildren bring a lot of happiness. After Christmas it’s birthdays; Susan 11 January, Andrew 13 January Betty 6 March, Alison Jane 12 March . Almost another life time gone. How time flies.

“Lonely, not when the day is swift,

With little things you like to do,

Nor when at night the Stars uplift

Your heart and soul to faith anew.

Not when you have a grief to bear,

And feel a friend’s hand gently laid

Upon your arm to love and care,

Could you be lonely and afraid?”

My life seemed so empty with Jim’s passing. In 1953 I married again, not for a husband. We were both lonely, Charlie and I. I am afraid it didn’t suit my sons and family, but I had my life to live. We spent twenty one years of companionship and happiness. Charlie was a wonderful man in many ways. A man you could only get to know by living with him. On the 21 June 1974 Charlie passed away, so now I am alone again, but much richer for the experience of meeting Charlie and marrying him.

I have been a very lucky woman. I have had two men in my life, Jim my husband and Charlie a very good companion and husband. I have shared a great amount of happiness with my two boys and Jim. Like Jim’s granddad used to tell me – “Ruth, never be afraid to say your sorry. If you feel a bit edgy always count ten before you smack the children. Never owe any money. If you have a pound, never spend more than nineteen shillings and eleven pence – happiness; spend one pound and a penny – unhappiness. Granddad Rose was a grand old man. I do believe taking his advice brought me all my happiness and I have never had any debts owing all my life. Not even a weeks groceries.

New Beginnings

“It’s sad to say goodbye to folk

We’ve lived among for years.

And leaving a familiar place

May bring regrets and tears.

But friends await us everywhere,

No matter where we roam.

And, warmed by love, a strange new house

Will soon become a home.”

What a lot of changes in my life. At the beginning no cars, no Concorde, no planes, no water- toilets, no electric,no wireless, no television. Now we have everything, but not everyone seems to have the happiness we had. How you spend your time is more important than how you spend your money. You can always put money matters right but time is gone forever. People today seem intent on having material possessions without taking time off to enjoy what they possess. Perhaps we would be happier if we spent our time more wisely instead of spending our money.

Copyright © Avril Wood, 1996