Martha Naylor’s family, like many from the West Midlands, were part of a massive population shift to the developing coal mines and new housing in the Yorkshire Coalfield. This moving essay by a later member of her family has been offered by her grandson Peter Greenall of Kettering.

Peter made contact to enable Martha’s records of the loss of her son Wilfred Howson in WW1 to be displayed in support of his memorial in Flanders and the commemorative cross in St Oswald’s church yard.

Martha Howson (Naylor) and her son Wilfred

by Margaret (Peggy) Whittaker daughter of Florence Howson

It is possible that I have been doing Caroline an injustice in saying that she was unable to read or write. Often villages had Dame Schools where children were sent for a penny or so a week to ‘learn their letters’. In any event there is no doubt that her daughters, at least the two youngest could (I never remember meeting great aunt Lily). The hand in which my grandmother wrote her will was untutored and obviously not often used, but her will itself was clear and succinct. It is one of the few objects which I have that belongs to her.

Another which I use every day is a mahogany occasional table, unfortunately with its legs broken, but which I have had near me all my life. It was a wedding present to my grandmother from her mistress, according to mother, for as a matter of course, she went into service. Who the mistress was I have no idea, but it may have been one of the farmer’s wives in the district, or the wife of some professional man – vicar, doctor, etc. No more big houses far away from home! Her elder sister, Florence went into middle class service in Wakefield, and married the son of the house, thereby raising her status in the community.

Her elder sister, Florence went into middle class service in Wakefield, and married the son of the house, thereby raising her status in the community.

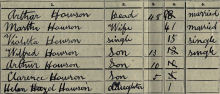

Not so Martha. I’m not sure when she married Arthur Howson, who was quite a few years older than herself, but going on what I do know, she must have been in her late teens or early twenties. Arthur was a handsome, fair, curly-headed miner from a family which mother insisted had lived in Methley since the year dot. Be that as it may, Howson is a very old Yorkshire name, which seems to cling to the Pennine areas. Mother said it should be easy to trace the Howson line in Methley, but though I would have liked to follow it up, I never had the opportunity. Once when doing a course on vernacular architecture, I was studying old documents, I came across a William Howson, farmer at Cracoe (1586), and another Thomas Howson of Coltparke (1663), and wondered vaguely if they were related to us.

I never knew my grandfather, but from what I have heard he was a hardworking, loving, impetuous, quick tempered man, who, according to mother, loved his horses almost more than he loved his children. The reference to horses may seem strange in a miner but Arthur’s father Thomas, had a haulage business in the Stack Garth at Methley and in those days, haulage meant horses. I expect Arthur grew up with them, and would help his father out even when he was employed down the pit. Certainly they had a horsebrake, a sort of forerunner of today’s motor coaches and used to take parties for trips. When I look on the map at some of the places they got to, I feel sorry for the poor horses. Askern Spa in one direction. Matlock Bath in the other. Nothing new under the sun. Our ancestors were just as fond of jaunting off as we are. Just the distances were less.

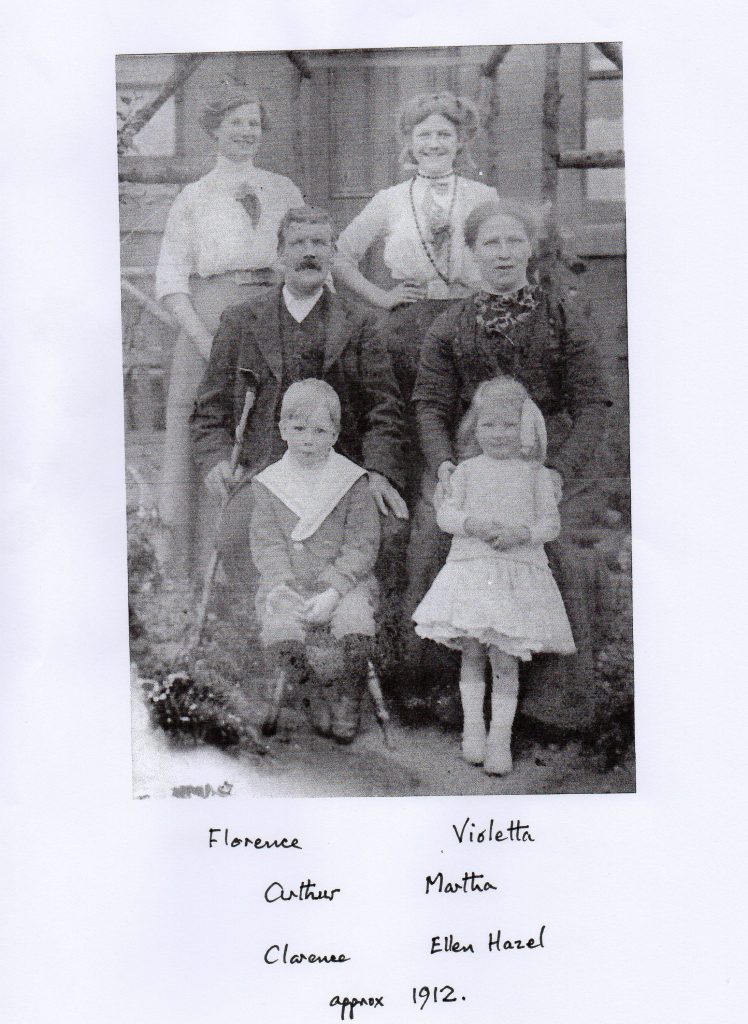

Though I don’t think Martha would have had much time for jaunting. She was too busy bearing a child almost every year for nineteen years ( I verified that from my Auntie Violet in case mother was exaggerating – a not entirely unknown occurrence). It seems that there were seventeen pregnancies of which there were two sets of twins – nineteen children in all. Mother was the oldest to survive. There is a photo somewhere of the two elder ones who died in infancy. So, as in those days, much of the upbringing of the younger children fell on the older ones, it is no wonder that both mother and auntie Vi when their turn came each had only one child.

Only another woman can imagine what it was like – one pregnancy following another with hardly time to recover from the last. And though Arthur was a good father and provider it was not all plain sailing and Martha had to take extra jobs from time to time to help eke out, sometimes in the fields at harvesting, but mainly nursing, for Martha was a wonderful nurse and midwife, and greatly in demand. I expect she was paid very little, for there was not a lot of money around in the country in those days.

There was also a dark mysterious episode which mother tended to slide over quickly, but eventually I pieced it together. Like most miners, Arthur liked his pint of beer, and would go down to the village pub on Saturday nights. It must have been on one of these occasions when he had had a drop too much and became quarrelsome, that he knifed his best friend. ‘Why?’ I wanted to know. Mother hedged. ‘He insulted your Grannie’ was all she would say. Why he should have done that I can’t imagine, unless it was to make some slighting reference to her her ability to produce offspring.

Like most miners, Arthur liked his pint of beer, and would go down to the village pub on Saturday nights. It must have been on one of these occasions when he had had a drop too much and became quarrelsome, that he knifed his best friend. ‘Why?’ I wanted to know. Mother hedged. ‘He insulted your Grannie’ was all she would say. Why he should have done that I can’t imagine, unless it was to make some slighting reference to her her ability to produce offspring.

Whatever it was, the upshot was that Arthur went to prison, and when a man went to prison in those days the whole family suffered. No handouts from social security in those days to make up missing wages, and not only that, they were thrown out of the house they lived in. According to mother, Arthur’s brothers and families who also lived in estate houses had to get out.  I think that that must have been when they moved to 6, Foxholes Row from Castleford. That must have been the family’s darkest hour.

I think that that must have been when they moved to 6, Foxholes Row from Castleford. That must have been the family’s darkest hour.

How long he was in prison, I don’t know, but Arthur certainly went back to the Savile Pit. (Perhaps it was a respite for Martha from having babies while he was there – there’s a silver lining in every cloud!) Out of all the babies the only ones to live to be adult were three boys and three girls. Florence, Violette, Wilfred, Arthur, Clarence and Helen Hazel (Nellie). Another one, Leonard, lived to be about eight but the others died in infancy. What can one say? Mother once said that Grannie had had TB in her youth, and the doctor had said that this was the reason for her losing so many children.

When the prison episode was, I can’t say. Florence often talked of her harsh childhood as deputy mother and general dogsbody, presumably while her mother went to work. She was a bright child and wanted to be a teacher, and the teachers at the church school at Methley were anxious to keep her on as a pupil teacher. Unfortunately this was not to be. Family pressures and finances demanded that she leave school at thirteen and go into service. Her sister Vi followed two years later, and as all wages were handed over to Martha, there must have been some easing of financial problems before the first world war.

In fact, Flo, Vi and small Nellie were on their first holiday ever in 1913 when tragedy struck. They were called home from Blackpool by the news that their father had been involved in an accident at work. For 48 hours he was buried under a roof fall of coal at the pit. This must have been in 1913, because although his spine was broken, he lived for another year and died just before the outbreak of war.

Thus Martha was left to bring up three teenage boys and a small girl on her own, the two elder ones away in service. Martha must have thought at first that the war was a remote thing which wouldn’t affect her, for her eldest son was under age as well as being in a reserved occupation, coal mining. But not for long. Wilfred wanted to be in, and enlisted under age. Martha got him out of the army, but by then he was of age and went into the Yorks and Lancs Regiment. He was soon in France and in the thick of things.

1917 must have been a memorable year for Martha and her family.  In February, her first child was married. My mother and father were married when my father was on a weeks leave from France. A few months later he was missing for six weeks after a gas attack at Cambrai. Hardly had the good news arrived that he was recovering in hospital, than the telegram that every family in those days dreaded, arrived. Wilf had been killed by a sniper while taking supplies to the front line. He was not yet nineteen and had already been wounded twice before.

In February, her first child was married. My mother and father were married when my father was on a weeks leave from France. A few months later he was missing for six weeks after a gas attack at Cambrai. Hardly had the good news arrived that he was recovering in hospital, than the telegram that every family in those days dreaded, arrived. Wilf had been killed by a sniper while taking supplies to the front line. He was not yet nineteen and had already been wounded twice before.

Now Martha was left again without a breadwinner. The two remaining boys were children, (Martha must have been thankful in so many ways that they were too young for the army), and so was Nellie, the youngest girl. Flo’ the eldest, was now married and Vi who had been doing war work, became ill from its effects. Martha herself went into a factory making shells, earning incidentally, more money than she had seen in her life before. She also took in lodgers and eventually as they became old enough, the boys went down the pit. And so they managed to the end of the war.

In 1919 my father came home from the war, jobless, of course, and without a home of his own, so the young couple were obliged to live with Martha until he got one. The little house must have been overcrowded. At some time Martha had a breakdown. There is a photo of her somewhere of her in a group at a convalescent home. But at some time after the war she was able to take a pilgrimage to the battlefields to find Wilf’s grave – her only trip abroad, or even holiday as far as I know.

Vi married Edward Fenwick (Uncle Teddy) in 1920.  In May 1921 Martha became a grandmother when I arrived on the scene, to be followed six weeks later by my cousin Vera. So for six years of my life, it overlapped my grandmother’s. I wish I could say I remember them clearly, but only vague shadows remain from those days. Walking with my parents from the bus down Park Lane to Foxholes (apparently I caused amusement by saying that it must be elastic because it stretched a long way – but I don’t remember that even. Sitting on my grannies lap which was covered with some black shiny material from which I kept sliding. And finally her coffin resting on the table before the funeral, from which I was excluded and had to stay with a neighbour.

In May 1921 Martha became a grandmother when I arrived on the scene, to be followed six weeks later by my cousin Vera. So for six years of my life, it overlapped my grandmother’s. I wish I could say I remember them clearly, but only vague shadows remain from those days. Walking with my parents from the bus down Park Lane to Foxholes (apparently I caused amusement by saying that it must be elastic because it stretched a long way – but I don’t remember that even. Sitting on my grannies lap which was covered with some black shiny material from which I kept sliding. And finally her coffin resting on the table before the funeral, from which I was excluded and had to stay with a neighbour.

A tragic and hardworking life. Yet those who knew her loved her dearly and always said what a wonderful person she was. Honest, straightforward and wonderfully compassionate. Although she had so little herself, she was the first person people in trouble thought of and she never let them down.

Of her actual death, I remember little, probably because in the weeks running up to it I was in isolation hospital with diphtheria. Between my birth and her death I suppose financially things would have been easier. She had two lads working, a permanent lodger (Arthur Lumb) and his little boy. Her two eldest daughters were settled with homes of their own. She particularly liked to visit my parents, where she got more of a rest from family cares than anywhere else. Her nursing skills were always in demand and in a way they helped to kill her.

In the latter half of 1927 Martha had been spending much of her time between Methley, where she still had a family to look after, and Sheffield, where her nephew, Albert Blackburn, son of her sister Florence, was dying of cancer. Today, with a car the journeys she had to make would have been fairly easy. Then, changing from buses to trains to trams countless times in one journey and hanging about on draughty stations and at bus stops in winter could have been anything but fun. She would also have stopped off at Woodlands, near Doncaster, where we lived to gather news of my progress, and calm my mother (diphtheria was a life threatening disease in those days) – ordinary people did not have telephones in those days.

I’m not sure of the timing, but I know I came out of hospital a few days before Christmas and within a few weeks Granny had died at Sheffield – so very shortly after Albert! How awful for Florence – her son and her sister to die almost together! Granny had caught pneumonia, then a killer disease with no antibiotics. She was 56 and exhausted by her struggling with life. Mother said that the doctor said to her. ‘Fight, Martha, fight, you can win through.’ She replied, ‘Why? I shall only have to go through it all again.’ Mother also said that Granny asked her to sing ‘Abide With Me’ as she was dying. I don’t know how she managed it. It always makes me cry under normal circumstances.

How awful for Florence – her son and her sister to die almost together! Granny had caught pneumonia, then a killer disease with no antibiotics. She was 56 and exhausted by her struggling with life. Mother said that the doctor said to her. ‘Fight, Martha, fight, you can win through.’ She replied, ‘Why? I shall only have to go through it all again.’ Mother also said that Granny asked her to sing ‘Abide With Me’ as she was dying. I don’t know how she managed it. It always makes me cry under normal circumstances.

My mother was very shaken by her mother’s sudden death, for they had been very close, and in many ways had been through a lot together. Fifty-six was young even in those days and though my Uncle Arthur married soon after and lived in Granny’s house, our visits to Methley after that were very few and far between.